The diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome is by the process of exclusion. When we can not find the reason for burning mouth symptoms, the disease is diagnosed as burning mouth syndrome.

The characteristic symptom is a burning or scalding sensation of the tongue. Less frequently, we can find the coincident symptoms in hard palate and mucosal aspect of the lips. Additionally, patient may complain of a sensation of dry mouth with increased thirst, change in taste, such as a bitter or metallic taste or loss of taste. There may also be tingling, stinging or numbness in the mouth.

These symptoms can cause little inconvenience in mild cases. In severe cases, they can prevent patients from conducting normal daily activities. It has been found that in extreme cases, patients may show suicidal tendencies.

In most cases, the burning sensation starts mild in the morning and increases in intensity as the day progresses. This type of presentation has the best prognosis.

- parafunctional habits, for example, unconsciously rubbing the tongue against the adjacent teeth and the hard palate which can cause traumatic abrasion of the filiform papillae on its dorsal surface

- dry mouth

- halitosis

- dysgeusia; most commonly a metallic taste

How will you diagnose and manage burning mouth syndrome

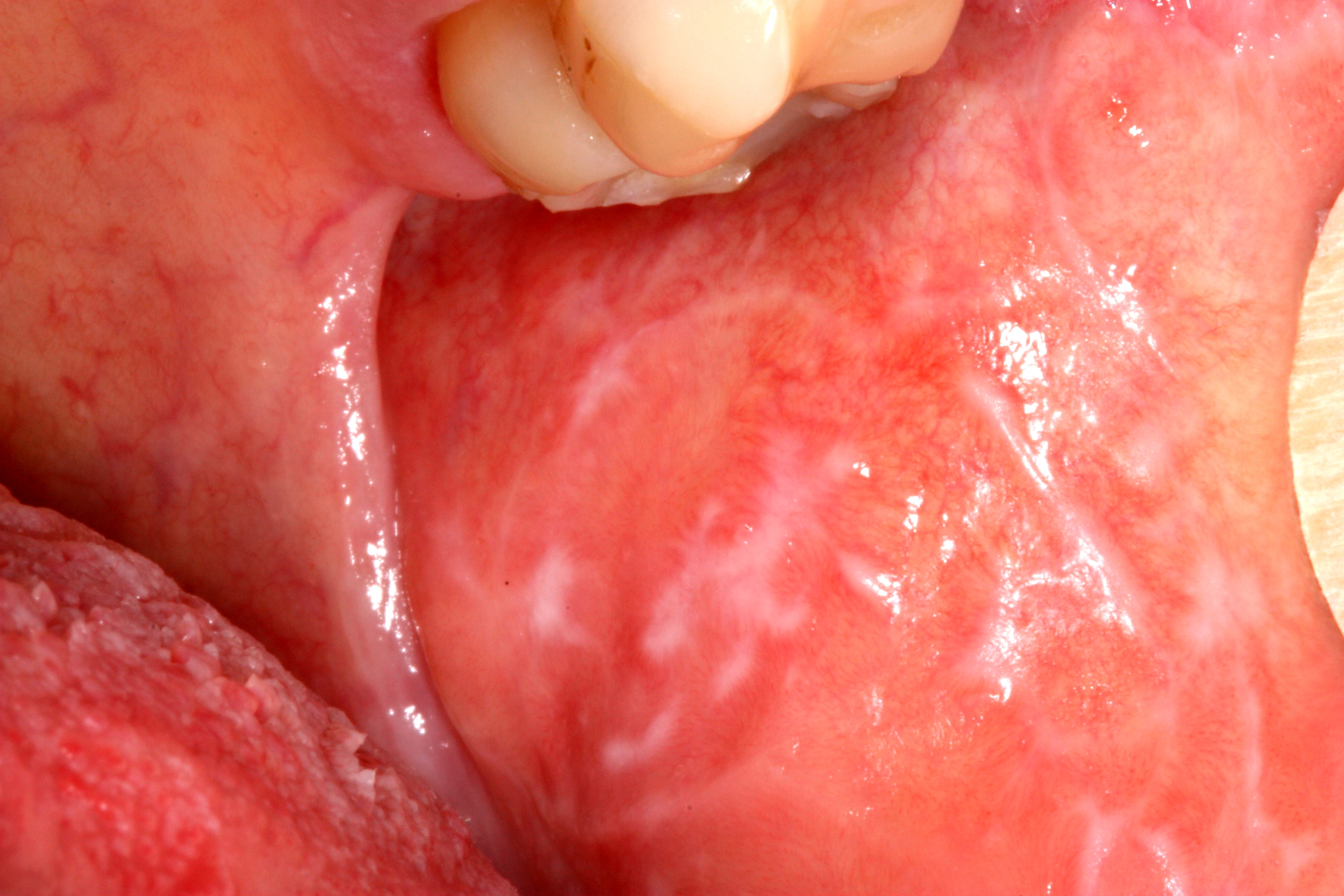

- local causes, for example, mucocutaneous conditions, fungal infections, rough dental surfaces

- systemic causes, for example, diabetes mellitus

- hypersensitivity to dental materials. Patients may say that he feels the problem is prosthesis-related. Hypersensitivity can be identified with skin patch testing, but rarely required

- drugs, for example, drugs that cause sensory neuropathy, taste aberrations or salivary gland hypofunction