Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for invasive dental procedures that involve the manipulation of gingival tissue or periapical region or perforation of the mucosa when performed on high-risk individuals. Australian guidelines have provided a list of dental procedures that are likely to cause a high incidence of bacteraemia that always require prophylaxis. These are as follows:

- Tooth extraction.

- Periodontal surgery, subgingival scaling and root planning.

- Replantation of avulsed teeth.

- Other surgical procedures such as implant placement or apicoectomy.

Procedures that cause a moderate incidence of bacteraemia might be considered for prophylaxis if multiple procedures are being conducted, in cases where the procedure is prolonged, or in the setting of periodontal disease.

Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for procedures with a low possibility of bacteraemia such as:

- Local anaesthetic injections.

- Dental X-rays.

- Treatment of superficial caries.

- Orthodontic appliance placement and adjustment.

- Following shedding of deciduous teeth.

- After lip or oral trauma.

Patient Selection

The current infective endocarditis/valvular heart disease guidelines [2] state that use of preventive antibiotics before certain dental procedures is reasonable for patients with:

- prosthetic cardiac valves, including transcatheter-implanted prostheses and homografts;

- prosthetic material used for cardiac valve repair, such as annuloplasty rings and chords;

- a history of infective endocarditis;

- a cardiac transplant with valve regurgitation due to a structurally abnormal valve;

- the following congenital (present from birth) heart disease:

- unrepaired cyanotic congenital heart disease, including palliative shunts and conduits

- any repaired congenital heart defect with residual shunts or valvular regurgitation at the site of or adjacent to the site of a prosthetic patch or a prosthetic device

AP for a dental procedure not suggested [3]

- Implantable electronic devices such as a pacemaker or similar devices

- Septal defect closure devices when complete closure is achieved

- Peripheral vascular grafts and patches, including those used for

hemodialysis

- Coronary artery stents or other vascular stents

- CNS ventriculoatrial shunts

- Vena cava filters

- Pledgets

Paediatric Patients

Congenital heart disease can indicate that prescription of prophylactic antibiotics may be appropriate for children. It is important to note, however, that when antibiotic prophylaxis is called for due to congenital heart concerns, they should only be considered when the patient has:

- Cyanotic congenital heart disease (birth defects with oxygen levels lower than normal), that has not been fully repaired, including children who have had a surgical shunts and conduits.

- A congenital heart defect that's been completely repaired with prosthetic material or a device for the first six months after the repair procedure.

- Repaired congenital heart disease with residual defects, such as persisting leaks or abnormal flow at or adjacent to a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device[2].

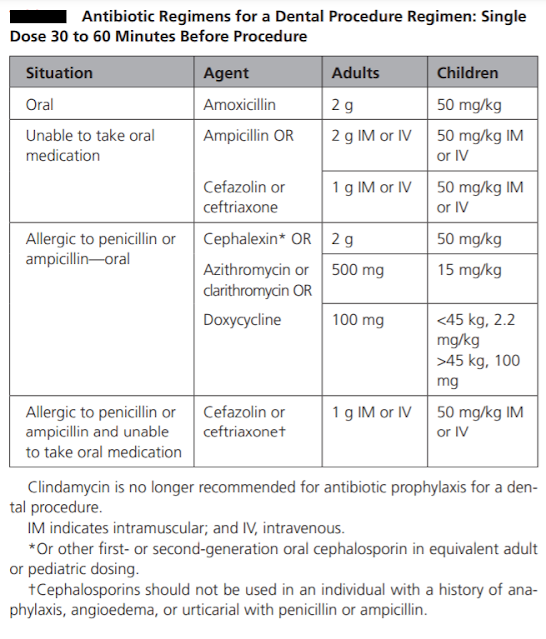

The prophylactic antibiotic should be effective against viridans group streptococci. The guidelines recommend 2 grams of amoxicillin given orally as a single dose 30-60 minutes before the procedure as the drug of choice for infective endocarditis prophylaxis. It has bactericidal activity against streptococci and enterococci. It reaches peak concentrations within one to two hours of oral administration, it has a short half-life of 1.5 hours, but therapeutic levels are maintained for nearly six hours. It has high oral bioavailability. The usual paediatric dosage is 50 mg/kg, with a maximum up to 2 gr. If the patient is unable to take oral medications, parenteral administration of 2 gr amoxicillin or ampicillin is considered as an alternative.

Oral or parenteral administration of cephalexin 2 gr for adults or 50 mg/kg for children, or parenteral administration of cefazolin or ceftriaxone 1 gr i.m./i.v. for adults or 50 mg/kg i.m./i.v for children are other alternatives. Cephalexin can be replaced by another first- or second-generation oral cephalosporin of equivalent dosage.

In patients hypersensitive to penicillin, guidelines are in agreement that the alternative drug of choice is clindamycin 600 mg (15-20 mg/kg up to 600 mg for children). It can be administered orally or intravenously 30-60 minutes before the procedure (as per European association of cardiologist [2], not as per ADA or AHA-see table). Clindamycin is a bacteriostatic protein synthesis inhibitor. Peak serum concentrations are achieved within 45 to 60 minutes after oral administration. Clindamycin is effective against streptococci and methicillin-sensitive staphylococci. However, some studies have questioned the potency of clindamycin prophylaxis. While ESC guidelines recommend solely clindamycin in penicillin-allergic patients, the AHA and Australian guidelines provide a variety of alternatives in this group of patients. The AHA guidelines recommend macrolides, 500 mg of azithromycin or clarithromycin (15 mg/kg for children). The Australian guidelines recommend glycopeptides; however, the ESC guidelines do not recommend glycopeptides and fluoroquinolones due to the lack of evidence on their efficacy. Cephalosporins should be refrained from use in patients who have encountered anaphylaxis, angioedema or urticaria related to penicillins.

It is important to administer prophylaxis before the procedure so that minimal inhibitory concentrations of the drugs will be present from the beginning of the procedure. If the patient cannot receive a prophylactic antibiotic before the procedure, it can be administered up to two hours after the procedure; however, delay in the treatment might lead to increased bacteraemia. If the patient needs multiple interventions, prophylaxis should be repeated with each. It is advised to finish necessary interventions in one or two sessions if possible. Given that consecutive exposures to the same antibiotic increase resistance rates, the healthcare provider might opt to choose different antibiotics for subsequent sessions. These might be the second-line alternative therapies mentioned in the guidelines or administering the patient a combination beta lactamase inhibitor such as amoxicillin-clavulanate or sulbactam-ampicillin. If the patient is already on antibiotic therapy with penicillins, the operation could be delayed until after the cessation of the antibiotic and restoration of the oral flora. If this is not possible, an alternative group of antibiotics could be preferred.

Ref:

1. https://www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-16/vol16no33#:~:text=The%20prophylactic%20antibiotic%20should%20be,choice%20for%20infective%20endocarditis%20prophylaxis.

2. https://www.ada.org/resources/research/science-and-research-institute/oral-health-topics/antibiotic-prophylaxis

3.https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000969