The third molars are the most common teeth that are found to be impacted. This article will provide and introduction to this topic. The difference between simple and surgical extraction along with the aetiologies and frequency of third molar impaction are explained in a simple way.

A coaching institution for ADC examination, ORE and Government dental job exams.

Introduction to Third Molar Surgery: Part-2 Indications and Contraindication

Mandibular Third Molars

According to George Dimitroulis, there are common and uncommon reasons for the removal of the mandibular third molar.

Iridium Course Schedule

A 20 Weeks Course for ADC Part 1 exam

Oral Hygiene

Regular oral hygiene by mechanical brushing and cleaning between the teeth removes soft dental plaque. When dental plaque becomes mineralised (calculus), it must be removed by a dental practitioner. Dental plaque and calculus can cause periodontal disease (eg gingivitis) and dental caries.

Frequent exposure to dietary sugar and carbohydrates leads to an increase in the risk of dental caries. Avoid sucrose in sticky forms and limit other sugars (eg acidic drinks) and carbohydrates as snacks between meals.

Avoid drinks other than water at bedtime after brushing teeth (including milk, formula and expressed breastmilk)—saliva flow diminishes during sleep and the sugar from the drink remains on the teeth overnight. This is a common cause of dental caries in children and the elderly.

Interdental cleaning

Interdental cleaning using floss or interdental brushes is recommended once each day before brushing the teeth. Brushing teeth with a toothbrush does not remove plaque from between the teeth or below the gum line.

Dental floss can be used to wipe the interdental tooth surface to remove plaque (back and forth, then up and down several times on each tooth surface). Manual dental floss, floss-holding devices or automated flossing devices are available—the choice is based on personal preference or level of dexterity.

Interdental brushes areas effective as dental floss in plaque removal, and often more effective for debris removal. They require less dexterity than dental floss. Interdental brushes are particularly useful in patients with gum recession or disease, where the spaces between the teeth are larger.

Interdental wood sticks can remove food particles, but do not effectively remove plaque.

Water jets do not effectively remove plaque.

Tooth and tongue cleaning

Soft-bristle toothbrushes are recommended; hard-bristle toothbrushes are not more effective and can damage the gums and the softer root surface. Children younger than 6 years should use a children’s toothbrush. Powered toothbrushes with a rotation oscillation action are slightly more effective at plaque removal than manual brushes. Powered toothbrushes are useful for people with dexterity or disability problems, and for carers. Toothbrushes should be replaced once damaged or when the bristles become deformed.

Advise patients to use a fluoride-containing toothpaste; for recommended concentrations of fluoride in toothpaste. Toothpastes that do not contain fluoride provide little protection against dental caries. Toothpastes also contain other additives (eg abrasives, detergents, antibacterial, bleaches, remineralising agents).

Toothpastes that do not contain fluoride provide little protection against dental caries.

Advise patients to brush teeth for 2 minutes, twice each day with fluoride toothpaste. Toothpaste should be spat out and not swallowed to minimise fluoride ingestion; the mouth should not be rinsed to allow increased uptake of fluoride from the saliva.

Advise patients to brush or gently scrape the tongue, but not to brush or massage the gums.

Mouthwash

Mouthwash is usually not required as part of a standard oral hygiene routine, provided mechanical cleaning (toothbrushing, interdental cleaning) is performed properly. Mouthwash should not be used as substitute for proper mechanical teeth cleaning.

Fluoride-containing mouthwashes can be used as an additional source of fluoride for people at high risk of dental caries on the recommendation of a dentist.

Mouthwash that inhibits plaque formation (eg chlorhexidine) can be used for a short duration in addition to mechanical tooth cleaning, usually when pain associated with periodontal disease restricts mechanical cleaning (see Management of necrotising gingivitis and Gingivitis).

Alcohol-containing mouthwashes may be associated with oral cancer and are not recommended. See here for further information on mouthwashes.

Specialised oral hygiene

People with dental implants, bridges, crowns that are joined together, and orthodontic brackets should follow the oral hygiene advice from their dentist.

Denture hygiene

Dentures should be regularly cleaned twice a day to remove food particles and plaque. Advise patients to remove dentures from the mouth and clean them with warm water, mild soap and a toothbrush, denture brush or soft nail brush. Avoid cleaning dentures with hot water, toothpaste, kitchen detergents, laundry bleaches, methylated spirits, antiseptics or abrasives (unless instructed to by a dental practitioner). Patients should clean their gums and remaining teeth with a soft toothbrush and toothpaste.

Advise patients to place dentures in a dry environment overnight after cleaning them. Traditionally, it was recommended that dentures were kept in liquid overnight. However, allowing the cleaned denture to dry out at night is more effective for reducing yeast colonisation and plaque accumulation, compared with both denture cleansers and water. Although repeated cycles of hydration and dehydration can change the shape of the denture, these changes are small and not clinically significant.

Dentures should be cleaned then placed in a dry environment at night. If there is a build-up of hard deposits (tartar, calculus), dentures can be soaked overnight in a solution of white vinegar (diluted 1:4), then cleaned as usual. Advise patients to see their dentist for professional cleaning if hard deposits cannot be removed.

Denture-associated erythematous stomatitis is prevented by regular cleaning of the dentures and storing them in a dry environment overnight. Advise patients with denture-associated erythematous stomatitis to optimise denture hygiene—it can take 1 month for symptoms to improve; see Oral candidiasis and Candida-associated lesions for further information.

Ref: Therapeutic Guidelines Limited 2019 (www.tg.org.au)

Radiation Protection of Pregnant Women

Is there a safe level of radiation exposure for a patient during pregnancy?

Dose boundaries do not apply for radiation exposure of patients, since the decision to use radiation is reasonable depending upon the individual patient situation. When it has been decided that a medical procedure is justified, the procedure should be optimized. This means that the conditions should achieve the clinical purpose with the appropriate dose. Dose limits are determined only for the staff and not for patients.

Dental Amalgam: SAQs for Viva Voce

SAQ 1. A patient arrives at your office and expresses concern about mercury from dental amalgam causing her harm. What will you tell this patient to reassure her about the safety of amalgam?

ANSWER:

You will explain three facts of dental amalgam fillings:

(1) The mercury present in amalgam is not free. It is always tied up chemically in the dental amalgam matrix. It is never released into the body. The majority of bound mercury never leaves the dental amalgam mass.

Burning Mouth Syndrome

The diagnosis of burning mouth syndrome is by the process of exclusion. When we can not find the reason for burning mouth symptoms, the disease is diagnosed as burning mouth syndrome.

The characteristic symptom is a burning or scalding sensation of the tongue. Less frequently, we can find the coincident symptoms in hard palate and mucosal aspect of the lips. Additionally, patient may complain of a sensation of dry mouth with increased thirst, change in taste, such as a bitter or metallic taste or loss of taste. There may also be tingling, stinging or numbness in the mouth.

These symptoms can cause little inconvenience in mild cases. In severe cases, they can prevent patients from conducting normal daily activities. It has been found that in extreme cases, patients may show suicidal tendencies.

In most cases, the burning sensation starts mild in the morning and increases in intensity as the day progresses. This type of presentation has the best prognosis.

- parafunctional habits, for example, unconsciously rubbing the tongue against the adjacent teeth and the hard palate which can cause traumatic abrasion of the filiform papillae on its dorsal surface

- dry mouth

- halitosis

- dysgeusia; most commonly a metallic taste

How will you diagnose and manage burning mouth syndrome

- local causes, for example, mucocutaneous conditions, fungal infections, rough dental surfaces

- systemic causes, for example, diabetes mellitus

- hypersensitivity to dental materials. Patients may say that he feels the problem is prosthesis-related. Hypersensitivity can be identified with skin patch testing, but rarely required

- drugs, for example, drugs that cause sensory neuropathy, taste aberrations or salivary gland hypofunction

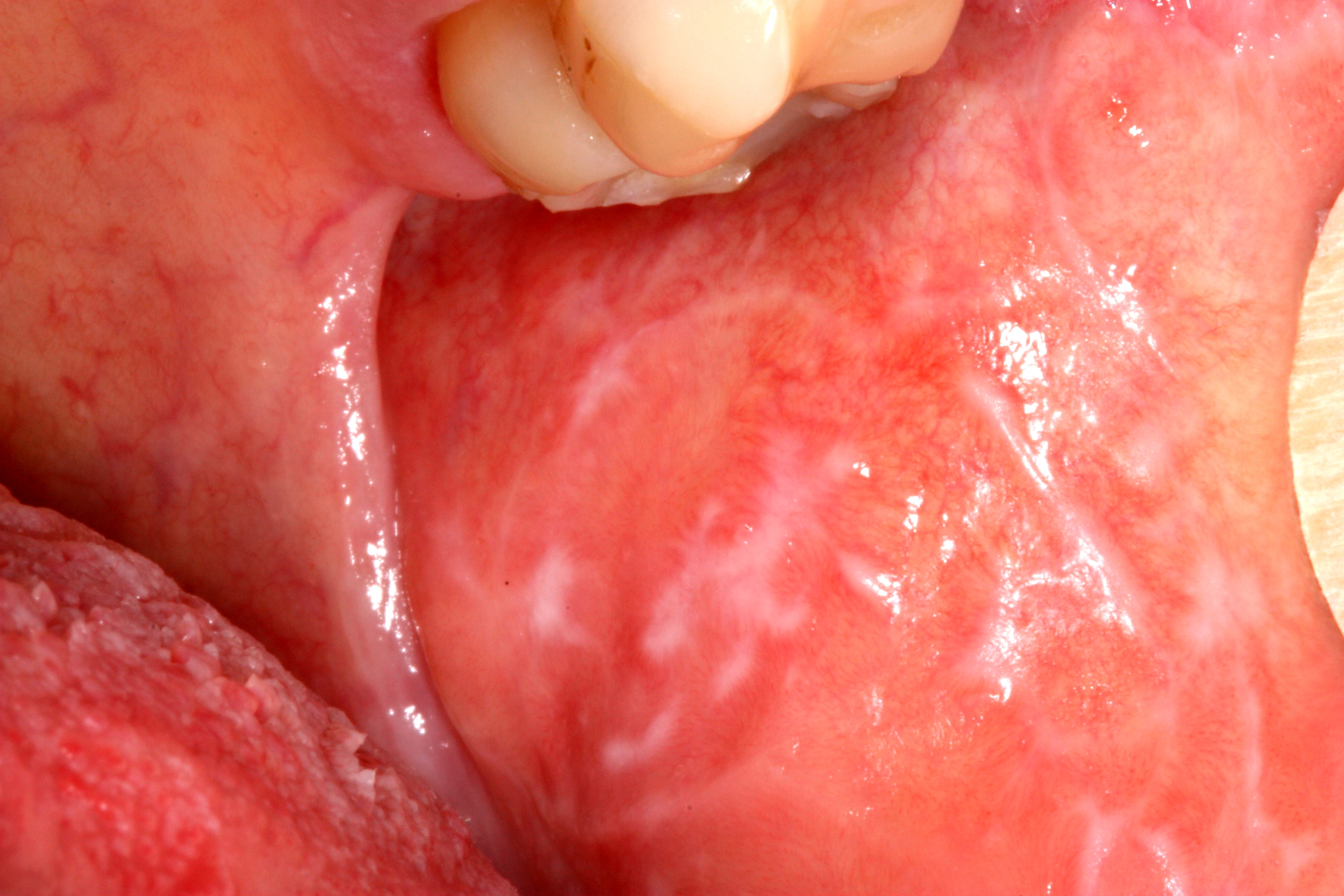

Oral Lichen Planus

Question: What is oral lichen planus?

Answer: It is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects the skin, nails, hair, and mucous membranes, characterised by purplish, itchy, flat eruptions.

Question: How common is the condition?

Answer: It is a common condition in India. Its cases are reported more than 10 lakh per year in India.

Question: How much time does it need for recovery?

Answer: It can last several years or remains lifelong.

Question: Is the condition treatable?

Answer: Treatments can help manage conditions. There is no known cure present.

Question: Does diagnosis require lab tests or imaging?

Answer: Its diagnosis rarely requires lab tests or imaging.

Condition Highlights

- It commonly occurs for ages 35-50.

- It is more common in females.

- Family history may increase likelihood to occur.

Assessment of oral mucosal disease

Oral mucosal lesions are common. They can be due to physiological changes or a local disease. They may also be an oral manifestation of a skin condition, an adverse drug reaction or systemic disease, for example, gastrointestinal disease. To manage an oral mucosal disease successfully one requires an accurate diagnosis.

Now the question arises, how will we get an accurate diagnosis?

The correct answer is, by a thorough assessment of oral mucosa for a lesion.

Assessment for an oral mucosal lesion involves taking a full patient history. This includes a medication history too. Next we need to perform a thorough extraoral and intraoral examination and use diagnostic investigations where appropriate. One should have a high index of suspicion for oral cancer.

To recognise oral cancer one should be familiar with the risk factors for oral cancer. You can see the “Oral Cancer” topic to know about risk factors for oral cancer. You should also thoroughly know the red flag features of oral cancer. If any 'red flag' features are present or the diagnosis is not clear or the patient has not responded to initial treatment, early referral to an appropriate specialist is required. An oral medicine specialist is the most appropriate specialist to diagnose and manage oral mucosal disease, but may not be accessible. Therefore, an oral surgeon, dermatologist or otorhinolaryngologist are other options.

Failure to respond to initial treatment, an unclear diagnosis or the presence of any suspicious features could indicate malignancy and warrant early referral.

‘Red flag’ features of oral mucosal disease

oral ulcers that have lasted for more than 2 weeks

orals ulcers that recur

nontraumatic oral ulcers in children

pigmented lesions on the oral mucosa

red, white or mixed red and white lesions on the oral mucosa of unknown origin or with features of potentially malignant disease, such as: induration, ulceration with rolled margins, fixation to underlying tissues, lesions in high-risk sites (eg lateral tongue, floor of mouth)

facial or oral paraesthesia

persistent oral mucosal discomfort with no obvious cause

lumps or swellings, including lymphadenopathy

swelling, pain or blockage of a salivary gland, suggestive of salivary gland disease

suspected allergy or adverse reaction to dental materials for example oral lichenoid lesion, dry mouth that is not adequately relieved with artificial salivary products and nonpharmacological methods and dry mouth caused by systemic disease

suspected oral manifestations of systemic disease, for example, syphilis, Behçet syndrome, HIV, inflammatory bowel disease, lichen planus, pemphigoid

lesions occurring in immunocompromised patients, for example, patients with neutropenia or HIV infection

Some oral mucosal diseases are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, particularly oral potentially malignant disorders and oral cancer. Oral potentially malignant disorders include:

- oral leukoplakia

- oral erythroplakia

- chronic hyperplastic candidiasis

- actinic cheilitis

- oral lichen planus

- oral submucous fibrosis

- discoid lupus erythematosus

- dyskeratosis congenita

- epidermolysis bullosa

Oral potentially malignant disorders can become malignant at the site of the lesion, but also predict an increased risk of cancer at other sites in the mouth, even in clinically normal appearing oral mucosa.

The following conditions can be managed in general practice, provided there are no 'red flag' features present that would warrant referral:

recurrent aphthous ulcerative disease

traumatic oral ulcers

oral candidiasis

angular cheilitis

oral mucocutaneous herpes simplex virus

dry mouth

oral mucositis

amalgam tattoo

geographic tongue

hairy tongue.

There are physiological causes of oral mucosal discolorations, for example, Fordyce spots which are ectopic sebaceous glands and leukoedema, that do not require active management.

Ref:

Therapeutic guidelines (oral & dental) 2019

Acute suppurative sialadenitis

Acute suppurative sialadenitis (including parotitis) is usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus. But sometimes it may be polymicrobial in adults. In acute suppurative sialadenitis, the glands are enlarged, often hot and tense, and pus may be expressed from the Stensen's duct. The patient is usually systemically unwell, dehydrated and has difficulty swallowing.

| Intraoral view of purulence emanating from the parotid duct orifice in a patient with acute suppurative parotitis [1]. |

Management

- urgent referral to hospital for surgical review

- rehydration

- culture and susceptibility testing of blood samples if the swelling is fluctuant, intraductal or surgical drainage; send pus for culture and susceptibility testing

- antibiotic therapy, given intravenously initially then orally once the patient can swallow.

If S. aureus is identified in a blood culture, treat as S. aureus bacteraemia. If the results of blood culture indicate a polymicrobial bacteraemia, take expert advice.

Intravenous antibiotic therapy for acute suppurative sialadenitis

Initiate empirical antibiotic therapy for acute suppurative sialadenitis in conjunction with local intervention or drainage. Use flucloxacillin 2 g (in case of child: 50 mg/kg up to 2 g) intravenously, 6-hourly; afterwards you can switch to oral therapy once the patient can swallow.

- clindamycin 600 mg (child: 15 mg/kg up to 600 mg) intravenously, 8-hourly; switch to oral therapy once the patient can swallow OR

- lincomycin 600 mg (child: 15 mg/kg up to 600 mg) intravenously, 8-hourly; switch to oral therapy once the patient can swallow.

Oral continuation therapy for acute suppurative sialadenitis

- HealthJade

- Therapeutic Guidelines Australia 2019